The city of Corinth was located in southern Greece, the capital of what was the Roman province of Achaia, 45 miles from Athens.

This city was one of the best peopled and most wealthy of Greece. Its situation between two seas drew thither the trade of both the east and west. Its riches produced pride, ostentation, effeminacy, and all vices, the consequences of abundance.

The city was so well known for its immorality and vice that people of the time commonly referred to a person of loose morals as one who ‘behaved like a Corinthian’ (cf. 1 Corinthians 6:9-11; 1 Corinthians 6:15-18).

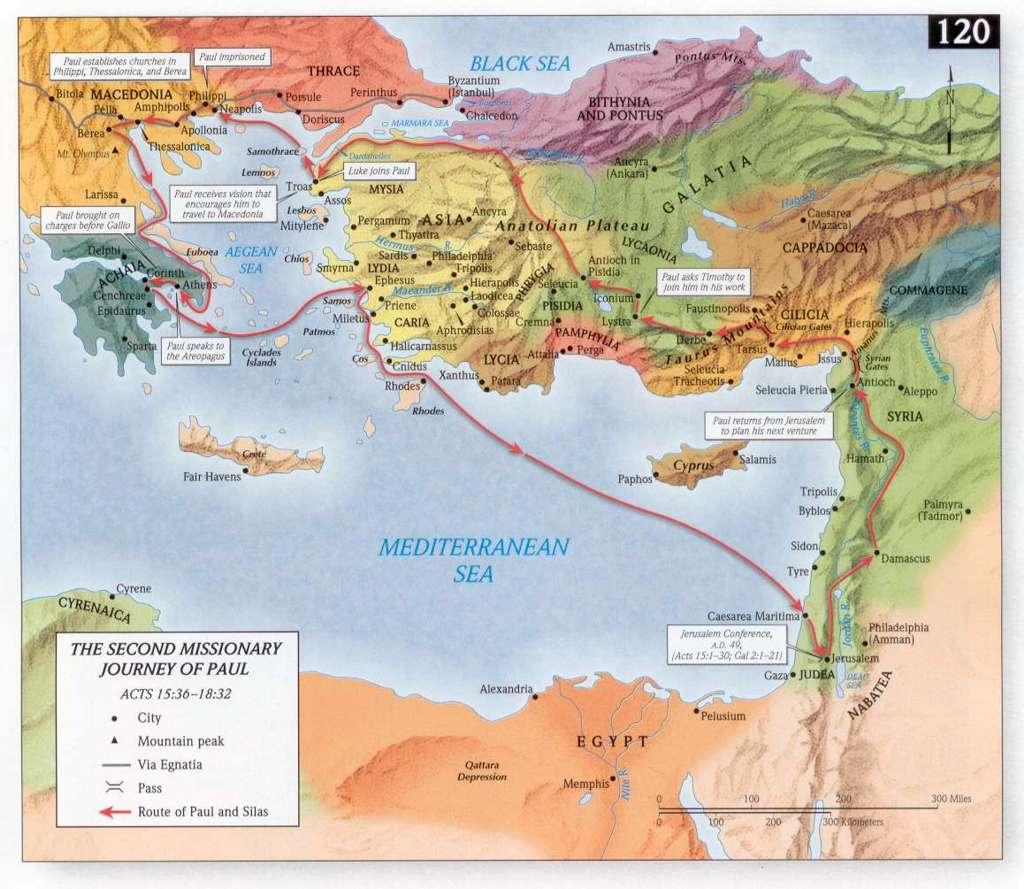

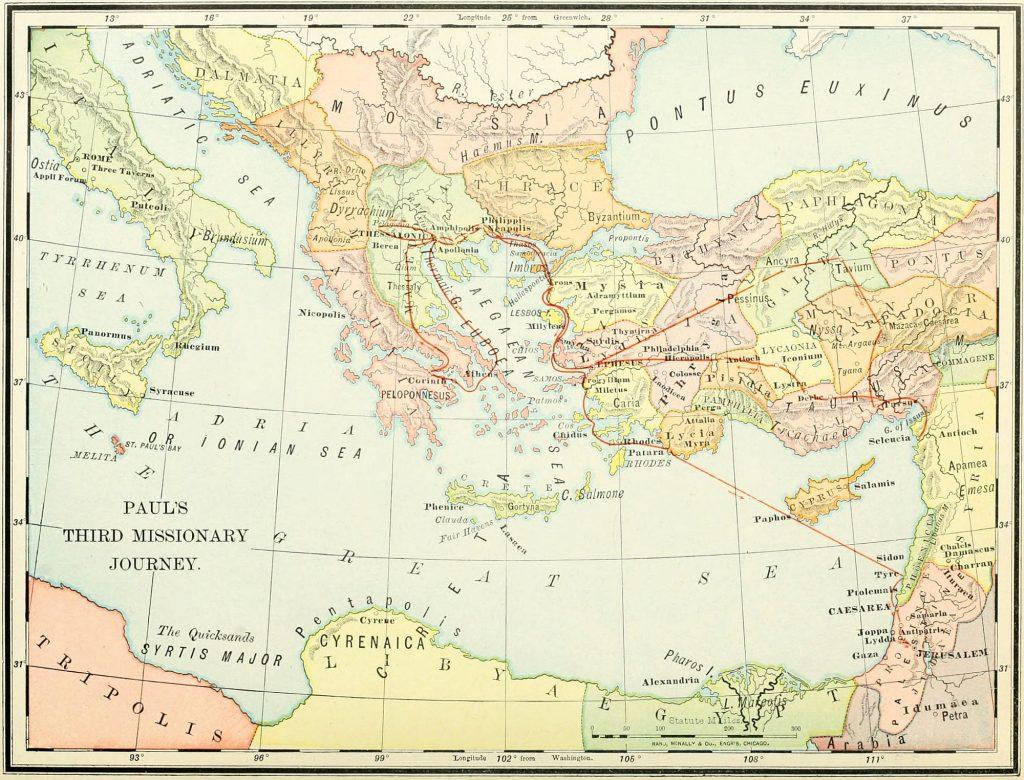

Paul’s first visit to Corinth was on his second missionary journey. He stayed eighteen months, and during that time he founded the Corinthian church ( Acts 18:1-17). Another church was established at Cenchreae, the seaport a few miles east ( Acts 18:18; Romans 16:1-2). Paul revisited the church at Corinth during his third missionary journey ( Acts 20:2-3). He also wrote the church a number of letters, two of which have been preserved in the New Testament.

History of Corinth

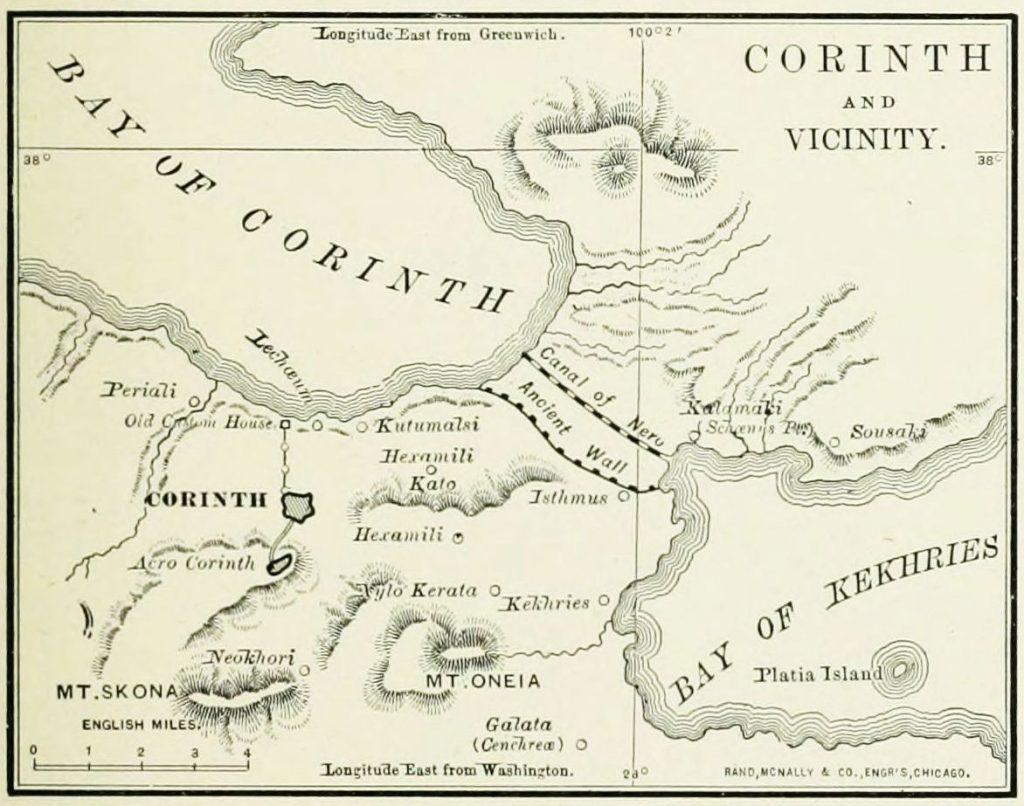

Corinth was located on the southwest end of the isthmus that joined the southern part of the Greek peninsula with the mainland to the north. The city was located on an elevated plain at the foot of Acrocorinth, a rugged hill reaching 1,886 feet above sea level. Corinth was a maritime city located between two important seaports: the port of Lechaion on the Gulf of Corinth about two miles to the north and the port of Cenchreae on the Saronic Gulf about six miles east of Corinth.

Corinth was an important city long before becoming a Roman colony in 44 B.C. In addition to the extant works of early writers, modern archaeology has contributed to knowledge of ancient Corinth. Excavation was begun by the American School of Classical Studies in Athens in 1896. From the results of this continuing work, important information has been published.

The discovery of stone implements and pottery indicates that the area was populated in the Late Stone Age. Metal tools have been found that reveal occupation during the Early Bronze Age (between 3000 B.C. and 2000 B.C.). The rising importance of Corinth during the classical period began with the Dorian invasion about 1000 B.C.

Located at the foot of Acrocorinth and at the southwest end of the isthmus, Corinth was relatively easy to defend. The Corinthians controlled the east-west trade across the isthmus as well as trade between Peloponnesus and the area of Greece to the north. The city experienced rapid growth and prosperity, even colonizing Siracuse on Sicily and the Island of Corcyra on the eastern shore of the Adriatic. Pottery and bronze were exported throughout the Mediterranean world.

For a century (about 350 to 250 B.C.) Corinth was the largest and most prosperous city of mainland Greece. Later, as a member of the Achaean League, Corinth clashed with Rome. Finally, the city was destroyed in 146 B.C. L Mummius, the Roman consul, burned the city, killed the men, and sold the women and children into slavery. For a hundred years the city was desolate.

Julius Caesar rebuilt the city in 44 B.C., and it quickly became an important city in the Roman Empire. An overland shiproad across the isthmus connected the ports of Lechaion and Cenchreae. Cargo from large ships was unloaded, transported across the isthmus, and reloaded on other ships. Small ships were moved across on a system of rollers. Ships were able, therefore, to avoid 200 miles of stormy travel around the southern part of the Greek peninsula. Today, a modern ship canal, constructed in A.D. 1881–1893, connects the two ports.

Description of Corinth in Paul’s Day

When Paul visited Corinth, the rebuilt city was little more than a century old. It had become, however, an important metropolitan center. Except where the city was protected by Acrocorinth, a wall about six miles in circumference surrounded it. The Lechaion road entered the city from the north, connecting it with the port on the Gulf of Corinth. As the road entered the city, it widened to more than twenty feet with walks on either side. From the southern part of the city a road ran southeast to Cenchreae.

Approaching the city from the north, the Lechaion road passed through the Propylaea, the beautiful gate marking the entrance into the agora (market). The agora was rectangular and contained many shops. A line of shops divided the agora into a northern and a southern section. Near the center of this dividing line the Bema was located. The Bema consisted of a large elevated speaker’s platform and benches on the back and sides. Here is probably the place Paul was brought before Gallio ( Acts 18:12-17 ).

Religions of Corinth

Although the restored city of Paul’s day was a Roman city, the inhabitants continued to worship Greek gods. West of the Lechaion road and north of the agora stood the old temple of Apollo. Probably partially destroyed by Mummius in 146 B.C., seven of the original thirty-eight columns still stand. On the east side of the road was the shrine to Apollo. In the city were shrines also to Hermes, Heracles, Athena, and Poseidon.

Corinth had a famous temple dedicated to Asclepius, the god of healing, and his daughter Hygieia. Several buildings were constructed around the temple for the sick who came for healing. The patients left at the temple terra cotta replicas of the parts of their bodies that had been healed. Some of these replicas have been found in the ruins.

The most significant pagan cult in Corinth was the cult of Aphrodite. The worship of Aphrodite had flourished in old Corinth before its destruction in 146 B.C. and was revived in Roman Corinth. A temple for the worship of Aphrodite was located on the top of the Acropolis. Strabo wrote concerning this temple.

And the temple of Aphrodite was so rich that it owned more than a thousand temple-slaves, courtesans, whom both men and women had dedicated to the goddess. And therefore it was also on account of these women that the city was crowded with people and grew rich; for instance, the ship-captains freely squandered their money, and hence the proverb, “Not for every man is the voyage to Corinth.”

Although the accuracy of Strabo has been questioned, his description is in harmony with the life-style reflected in Paul’s letters to the Corinthians.

Jewish worship also was a part of the religious life of the city. Paul began his Corinthian ministry in the synagogue in Corinth.

Church in Corinth

The church in Corinth consisted principally of non-Jews ( 1 Corinthians 12:2 ). Paul had no intention at first of making the city a base of operations ( Acts 18:1; Acts 16:9 , Acts 16:10 ); for he wished to return to Thessalonica ( 1 Thessalonians 2:17 , 1 Thessalonians 2:18 ).

His plans were changed by a revelation ( Acts 18:9 , Acts 18:10 ). The Lord commanded him to speak boldly, and he did so, remaining in the city eighteen months. Finding strong opposition in the synagogue he left the Jews and went to the Gentiles ( Acts 18:6 ). Nevertheless, Crispus, the ruler of the synagogue and his household were believers and baptisms were numerous ( Acts 18:8 ); but no Corinthians were baptized by Paul himself except Crispus, Gaius and some of the household of Stephanas ( 1 Corinthians 1:14 , 1 Corinthians 1:16 ) “the firstfruits of Achaia” ( 1 Corinthians 16:15 ). One of these, Gaius, was Paul’s host the next time he visited the city ( Romans 16:23 ).

Silas and Timothy, who had been left at Berea, came on to Corinth about 45 days after Paul’s arrival. It was at this time that Paul wrote his first Epistle to the Thessalonians ( 1 Thessalonians 3:6 ).

During Gallio’s administration the Jews accused Paul, but the proconsul refused to allow the case to be brought to trial. This decision must have been looked upon with favor by a large majority of the Corinthians, who had a great dislike for the Jews ( Acts 18:17 ). Paul became acquainted also with Priscilla and Aquila ( Acts 18:18 , Acts 18:26; Romans 16:3; 2 Timothy 4:19 ), and later they accompanied him to Ephesus.

Within a few years after Paul’s first visit to Corinth the Christians had increased so rapidly that they made quite a large congregation, but it was composed mainly of the lower classes: they were neither ‘learned, influential, nor of noble birth’ ( 1 Corinthians 1:26 ).

Paul probably left Corinth to attend the celebration of the feast at Jerusalem ( Acts 18:21 ). Little is known of the history of the church in Corinth after his departure. Apollos came from Ephesus with a letter of recommendation to the brethren in Achaia ( Acts 18:27; 2 Corinthians 3:1 ); and he exercised a powerful influence ( Acts 18:27 , Acts 18:28; 1 Corinthians 1:12 ); and Paul came down later from Macedonia.

His first letter to the Corinthians was written from Ephesus. Both Titus and Timothy were sent to Corinth from Ephesus ( 2 Corinthians 7:13 , 2 Corinthians 7:15; 1 Corinthians 4:17 ), and Timothy returned by land, meeting Paul in Macedonia ( 2 Corinthians 1:1 ), who visited Greece again in 56-57 or 57-58.

First Epistle To The Corinthians

Paul had been instrumental in converting many Gentiles ( 1 Corinthians 12:2) and some Jews ( Acts 18:8), notwithstanding the Jews’ opposition ( Acts 18:5-6), during his one year and a half sojourn. The converts were mostly of the humbler classes ( 1 Corinthians 1:26). Crispus, Erastus, and Gaius (Caius), however, were men of rank ( 1 Corinthians 1:14; Acts 18:8; Romans 16:23). 1 Corinthians 11:22 implies a variety of classes. The immoralities abounding outside at Corinth, and the craving even within the church for Greek philosophy and rhetoric which Apollos’ eloquent style gratified, rather than for the simple preaching of Christ crucified ( 1 Corinthians 2:1, etc.; Acts 18:24, etc.), as also the opposition of Judaizing teachers who boasted of having “letters of commendation” from Jerusalem the metropolis of the faith, caused the apostle anxiety.

The Judaizers depreciated his apostolic authority ( 1 Corinthians 9:1-2; 2 Corinthians 10:1; 2 Corinthians 10:7-8), professing, some to be the followers of the chief apostle, Cephas; others to belong to Christ Himself, rejecting all subordinate teaching ( 1 Corinthians 1:12; 2 Corinthians 10:7). Some gave themselves out to be apostles ( 2 Corinthians 11:5; 2 Corinthians 11:13), alleging that Paul was not of the twelve nor an eye-witness of the gospel facts, and did not dare to prove his apostleship by claiming support from the church (1 Corinthians 9). Even those who declared themselves Paul’s followers did so in a party spirit, glorying in the minister instead of in Christ. Apollos’ followers also rested too much on his Alexandrian rhetoric, to the disparagement of Paul, who studied simplicity lest aught should interpose between the Corinthians and the Spirit’s demonstration of the Savior (1 Corinthians 2).

Epicurean self-indulgence led some to deny the resurrection ( 1 Corinthians 15:32). Hence, they connived at the incest of one of them with his stepmother (1 Corinthians 5). The elders of the church had written to consult Paul on minor points: (1) meats offered to idols; (2) celibacy and marriage; (3) the proper use of spiritual gifts in public worship; (4) the collection for the saints at Jerusalem ( 1 Corinthians 16:1, etc.). But they never told him about the serious evils, which came to his ears only through some of the household of Chloe ( 1 Corinthians 1:11), contentions, divisions, lawsuits brought before pagan courts by Christian brethren against brethren ( 1 Corinthians 6:1). Moreover, some abused spiritual gifts to display and fanaticism (1 Corinthians 14); simultaneous ministrations interrupted the seemly order of public worship; women spoke unveiled, in violation of eastern usage, and usurped the office of men; even the Holy Communion was desecrated by reveling (1 Corinthians 11).

These then formed topics of his epistle, and occasioned his sending Timothy to them after his journey to Macedonia ( 1 Corinthians 4:17). In 1 Corinthians 4:18; 1 Corinthians 5:9, he implies that he had sent a previous letter to them; probably enjoining also a contribution for the poor saints at Jerusalem. Upon their asking directions as to the mode, he now replies ( 1 Corinthians 16:2). In it he also announced his design of visiting them on his way to and from Macedon ( 2 Corinthians 1:15-16), which design he changed on hearing the unfavorable report from Chloe’s household ( 1 Corinthians 16:5-7), for which he was charged with fickleness ( 2 Corinthians 1:15-17). Alford remarks, Paul in 1 Corinthians alludes to the fornication only in a summary way, as if replying to an excuse set up after his rebuke, rather than introducing it for the first time.

Before this former letter, he paid a second visit (probably during his three years’ sojourn at Ephesus, from which he could pass readily by sea to Corinth Acts 19:10; Acts 20:31); for in 2 Corinthians 12:14; 2 Corinthians 13:1, he declares his intention to pay a third visit. In 1 Corinthians 13:2 translated “I have already said (at my second visit), and declare now beforehand, as (I did) when I was present the second time, so also (I declare) now in my absence to them who have heretofore sinned (namely, before my second visit, 1 Corinthians 12:21) and to all others” (who have sinned since it, or are in danger of sinning). “I write,” the Alexandrinus, Vaticanus, and Sinaiticus manuscripts rightly omit; KJV “as if I were present the second time,” namely, this time, is inconsistent with verse 1, “this is the third time I am coming” (compare 2 Corinthians 1:15-16).

The second visit was a painful one, owing to the misconduct of many of his converts ( 2 Corinthians 2:1). Then followed his letter before the 1 Corinthians, charging them “not to company with fornicators.” In 1 Corinthians 5:9-12 he corrects their misapprehensions of that injunction. The Acts omits that second visit, as it omits other incidents of Paul’s life, e.g. his visit to Arabia ( Galatians 1:17-28). The place of writing was Ephesus ( 1 Corinthians 16:8). The English subscription “from Philippi” arose from mistranslating 1 Corinthians 16:5, “I am passing through Macedonia;” he intended ( 1 Corinthians 16:8) leaving Ephesus after Pentecost that year. He left it about A.D. 57 ( Acts 19:21). The Passover imagery makes it likely the date was Easter time ( 1 Corinthians 5:7), A.D. 57.

Just before his conflict with the beastlike mob of Ephesus, 1 Corinthians 15:32 implies that already he had premonitory symptoms; the storm was gathering, his “adversaries many” ( 1 Corinthians 16:9; Romans 16:4). The tumult ( Acts 19:29-30) had not yet taken place, for immediately after it he left Ephesus for Macedon. Sosthenes, the ruler of the Jews’ synagogue, after being beaten, seems to have been won by Paul’s love to an adversary in affliction ( Acts 18:12-17). Converted, like Crispus his predecessor in office, he is joined with Paul in the inscription, as “our brother.” A marvelous triumph of Christian love! Paul’s persecutor paid in his own coin by the Greeks, before Gallio’s eyes, and then subdued to Christ by the love of him whom he sought to persecute. Stephanas, Fortunatus, and Achaicus, were probably the bearers of the epistle ( 1 Corinthians 16:17-18); see the subscription.

Second Epistle To The Corinthians

Reasons for writing.

To explain why he deferred his promised visit to Corinth on his way to Macedonia ( 1 Corinthians 4:19; 1 Corinthians 16:5; 2 Corinthians 1:15-16), and so to explain his apostolic walk, and vindicate his apostleship against gainsayers ( 2 Corinthians 1:12; 2 Corinthians 1:24; 2 Corinthians 6:3-18; 2 Corinthians 7:2; 2 Corinthians 7:10; 2 Corinthians 7:11; 2 Corinthians 7:12).

Also to praise them for obeying his first epistle, and to charge them to pardon the transgressor, as already punished sufficiently ( 2 Corinthians 2:1-11; 2 Corinthians 7:6-16).

Also to urge them to contributions for the poor brethren at Jerusalem (2 Corinthians 8).

Time of writing

After Pentecost A.D. 57, when Paul left Ephesus for Troas. Having stayed for a time at Troas preaching with success ( 2 Corinthians 2:12-13), he went on to Macedonia to meet Titus there, since he was disappointed in not finding him at Troas as he had expected. In Macedonia he heard from him the comforting intelligence of the good effect of the first epistle upon the Corinthians, and having experienced the liberality of the Macedonian churches (2 Corinthians 8) he wrote this second epistle and then went on to Greece, where he stayed three months; then he reached Philippi by land about Passover or Easter, A.D. 58 ( Acts 20:1-6). So that the autumn of A.D. 57 will be the date of 2 Corinthians. Place of writing. Macedonia, as 2 Corinthians 9:2 proves. In “ASIA” (see) he had been in great peril ( 2 Corinthians 1:8-9), whether from the tumult at Ephesus ( Acts 19:23-41) or a dangerous illness (Alford).

Thence he passed by way of Troas to Philippi, the first city that would meet him in entering Macedonia ( Acts 20:1), and the seat of the important Philippian church. On comparing 2 Corinthians 11:9 with Philippians 4:15-16 it appears that by “Macedonia” there Paul means Philippi. The plural “churches,” however, ( 2 Corinthians 8:1) proves that Paul visited other Macedonian churches also, e.g. Thessalonica and Berea. But Philippi, as the chief one, would be the center to which all the collections would be sent, and probably the place of writing 2 Corinthians Titus, who was to follow up at Corinth the collection, begun at the place of his first visit ( 2 Corinthians 8:6). The style passes rapidly from the gentle, joyous, and consolatory, to stern reproof and vindication of his apostleship against his opponents. His ardent temperament was tried by a chronic malady ( 2 Corinthians 4:7; 2 Corinthians 5:1-4; 2 Corinthians 12:7-9).

Then too “the care of all the churches” pressed on him; the weight of which was added to by Judaizing emissaries at Corinth, who wished to restrict the church’s freedom and catholicity by bonds of letter and form ( 2 Corinthians 3:8-18). Hence, he speaks of ( 2 Corinthians 7:5-6) “rightings without” and “fears within” until Titus brought him good news of the Corinthian church. Even then, while the majority at Corinth repented and excommunicated, at Paul’s command, the incestuous person, and contributed to the Jerusalem poor fund, a minority still accused him of personal objects in the collection, though he had guarded against possibility of suspicion by having others beside himself to take charge of the money ( 2 Corinthians 8:18-28). Moreover, their insinuation was inconsistent with their other charge, that his not claiming maintenance proved him to be no apostle.

They alleged too that he was always threatening severe measures, but was too cowardly to execute them ( 2 Corinthians 10:8-16; 2 Corinthians 13:2); that he was inconsistent, for he had circumcised Timothy but did not circumcise Titus, a Jew among the Jews, a Greek among the Greeks ( 1 Corinthians 9:20, etc.; Galatians 2:3). That many of his detractors were Judaizers appears from 2 Corinthians 11:22. An emissary from Judaea, arrogantly assuming Christ’s own title “he that cometh” ( Matthew 11:3), headed the party ( 2 Corinthians 11:4); he bore “epistles of commendation” ( 2 Corinthians 3:1), and boasted of pure Hebrew descent, and close connection with Christ Himself ( 2 Corinthians 11:13; 2 Corinthians 11:22-23). His high-sounding pretensions and rhetoric contrasted with Paul’s unadorned style, and carried weight with some ( 2 Corinthians 10:10; 2 Corinthians 10:13; 2 Corinthians 11:6). The diversity in tone, in part, is due to the diversity between the penitent majority and the refractory minority. Two deputies chosen by the churches to take charge of the collection accompanied Titus, who bore this 2 Corinthians ( 2 Corinthians 8:18-22).