Samuel (Heb. Shemuel‘, שַׁמוּאֵל; Sept. and New Test. Σαμουήλ) was the last of judges over the Israel, and the first of the line of the prophets (Acts 13:20, Acts 3:24). He is known for anointing Saul and David as the first kings of Israel. The books of 1 Samuel and 2 Samuel in the Old Testament tell the story of his life and prophecies.

Name – Of this different derivations have been given

(1) שֵׁם אֵל, “name of God;” so apparently Origen (Euseb. H. E. 6, 25), i.q. Θεοκλητός.

(2) אֵל שׁוּם, “placed by God.”

(3) שָׁאוּל אֵל, “asked of God” (1Sa 1:20). Josephus (who gives this interpretation, Σαμούηλος, Ant. 5, 10, 3) ingeniously makes it correspond to the well-known Greek name Θεαίτητος.

(4) שׁמוּעִ אֵל, “heard of God.” This, which is the most obvious, may have the same meaning as the previous derivation, which is supported by the sacred text (1Sa 1:20).

Family and Birth (1 Samuel 1:1-28)

Samuel’s mother was Hannah and his father was Elkanah. Elkanah lived at Ramathaim in the district of Zuph (1 Samuel 1:1-2). His genealogy is also found in a pedigree of the Kohathites (1 Chronicles 6:3-15) and in that of Heman the Ezrahite, apparently his grandson (1 Chronicles 6:18-33).

According to the genealogical tables in Chronicles, Elkanah was a Levite – a fact not mentioned in the books of Samuel. The fact that Elkanah, a Levite, was denominated an Ephraimite is analogous to the designation of a Levite belonging to Judah (Judges 17:7, for example).

According to 1 Samuel 1:1–28, Elkanah had two wives, Peninnah and Hannah. Peninnah had children; Hannah did not. Nonetheless, Elkanah favored Hannah. Jealous, Penninah reproached Hannah for her lack of children, causing Hannah much heartache. Elkanah was a devout man and would periodically take his family on pilgrimage to the holy site of Shiloh.

On one occasion, Hannah went to the sanctuary and prayed for a child. In tears, she vowed that if she were granted a child, she would dedicate him to God as a nazirite. Eli, who was sitting at the foot of the doorpost in the sanctuary at Shiloh, saw her apparently mumbling to herself and thought she was drunk, but was soon assured of both her motivation and sobriety. Eli was the priest of Shiloh, and one of the last Israelite Judges before the rule of kings in ancient Israel. Eli blessed her and she returned home. Subsequently, Hannah became pregnant, later giving birth to Samuel, and praised God for his mercy and faithfulness.

After the child was weaned, she left him in Eli’s care, and from time to time she would come to visit her son.

Trained by Eli (1 Samuel 2:18-26)

From this time the child is shut up in the tabernacle. The priests furnished him with a sacred garment, an ephod, made, like their own, of white linen, though of inferior quality, and his mother every year, apparently at the only time of their meeting, gave him a little mantle reaching down to his feet, such as was worn only by high personages, or women, over the other dress, and such as he retained, as his badge, till the latest times of his life. He seems to have slept near the holy place (1Sa 3:3), and his special duty was to put out, as it would seem, the sacred candlestick, and to open the doors at sunrise.

Samuel’s Call (1 Samuel 3:2-18)

Samuel worked under Eli in the service of the shrine at Shiloh. One night, Samuel heard a voice calling his name (1 Samuel 3:2). Samuel initially assumed it was coming from Eli and went to Eli to ask what he wanted. Eli, however, sent Samuel back to sleep. After this happened three times, Eli realised that the voice was the Lord’s, and instructed Samuel on how to answer:

Go and lie down, and if he calls you, say, ‘Speak, Lord, for your servant is listening.’ (1 Samuel 3:9)

Once Samuel responded, the Lord told him that the wickedness of the sons of Eli had resulted in their dynasty being condemned to destruction. In the morning, Samuel was hesitant about reporting the message to Eli, but Eli asked him to honestly recount to him what he had been told by the Lord. Upon receiving the communication, Eli merely said that the Lord should do what seems right unto him.

Samuel grew up and “all Israel from Dan to Beersheba” came to know that Samuel was a trustworthy prophet of the Lord. (1 Samuel 3:19-21)

Samuel’s Civil Administration

When the feeble administration of Eli, who had judged Israel forty years, was concluded by his death, Samuel was too young to succeed to the regency; and the actions of this earlier portion of his life are left unrecorded. The ark, which had been captured by the Philistines, soon vindicated its majesty, and, after being detained among them seven months, was sent back to Israel. It did not, however, reach Shiloh, in consequence of the fearful judgment upon Beth-shemesh (1Sa 6:19), but rested in Kirjath-jearim for no fewer than twenty years (1Sa 7:2). It is not till the expiration of this period that Samuel appears again in the history.

Perhaps, during the twenty years succeeding Eli’s death, his authority was gradually gathering strength; while the office of supreme magistrate may have been vacant, each tribe being governed by its own hereditary phylarch. This long season of national humiliation was, to some extent, improved. “All the house of Israel lamented after the Lord;” (1 Samuel 7:2) and Samuel, seizing upon the crisis, issued a public manifesto, exposing the sin of idolatry, urging on the people religious amendment, and promising political deliverance on their reformation. The people obeyed, the oracular mandate was effectual, and the principles of the theocracy again triumphed (1Sa 7:3-4).

The tribes were summoned by the prophet to assemble in Mizpeh; and at this assembly of the Hebrew comitia, Samuel seems to have been elected regent (1Sa 7:6). Some of the judges were raised to political power as the reward of their military courage and talents; but Samuel was raised to the lofty station of judge, from his prophetic fame, his sagacious dispensation of justice, his real intrepidity, and his success as a restorer of the true religion. His government, founded not on feats of chivalry or actions of dazzling enterprise, which great emergencies only call forth, but resting on more solid qualities, essential to the growth and development of a nation’s resources in times of peace, laid the foundation of that prosperity which gradually elevated Israel to the position it occupied in the days of David and his successors.

This mustering of the Hebrews at Mizpeh on the inauguration of Samuel alarmed the Philistines, and their “lords went up against Israel.” (1Sa 7:7) Samuel offered a solemn oblation, and implored the immediate protection of the Lord. With a symbolical rite, expressive, partly of deep humiliation, partly of the libations of a treaty, the people poured water on the ground; they fasted; and they entreated Samuel to raise the piercing cry for which he was known in supplication to God for them. It was at the moment that he was offering up a sacrifice, and sustaining this loud cry, that the Philistine host suddenly burst upon them. He was answered by propitious thunder, an unprecedented phenomenon in that climate at that season of the year. A fearful storm burst upon the Philistines; the elements warred against them. “The Highest gave his voice in the heaven, hailstones and coals of fire.” The old enemies of Israel were signally defeated, and did not recruit their strength again during the administration of the prophet judge. (1Sa 7:8-11)

Exactly at the spot where, twenty years before, they had obtained their great victory, a stone was set up, which long remained as a memorial of Samuel’s triumph, and gave to the place its name of Ebenezer, “the Stone of Help,” which has thence passed into Christian phraseology, and become a common name of Nonconformist chapels (1Sa 7:12). The old Canaanites, whom the Philistines had dispossessed in the outskirts of the Judean hills, seem to have helped in the battle; and a large portion of territory was recovered (1Sa 7:14). This was Samuel’s first, and, as far as we know, his only, military achievement. But, as in the case of the earlier chiefs who bore that name, it was apparently this which confirmed him in the office of “judge”.

The presidency of Samuel appears to have been eminently successful. Its length is nowhere given in the Scriptures; but, from a statement of Josephus (Ant. 6, 13, 5), it appears to have lasted twelve years (B.C. 1105 -1093), up to the time of Saul’s inauguration.

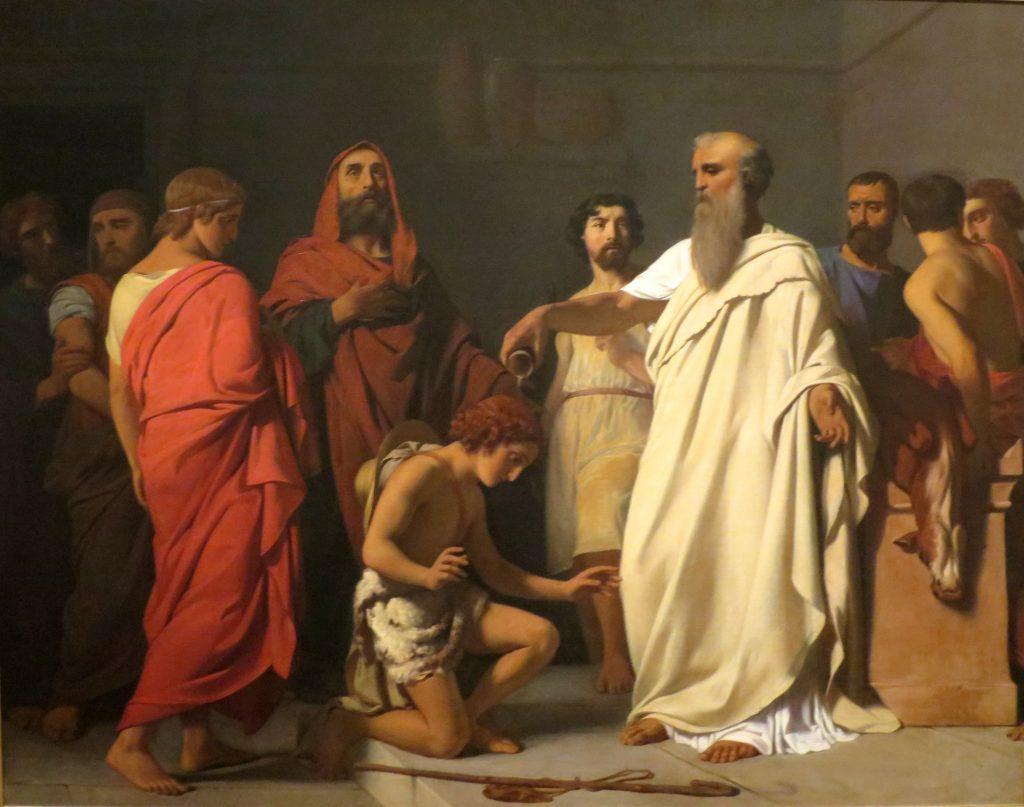

Anoint Saul as the first king of Israel

As Samuel grew old, his sons took over much of the administration. But instead of resisting the social corruption that had become widespread through the people’s disobedience to God, they contributed to it ( 1 Samuel 8:1-3).

In search for improved conditions, the people asked Samuel to bring the old system to an end and give them a king after the pattern that existed in other nations. This was not so much a rejection of Samuel as a rejection of God. The people’s troubles had come not from the system of government, but from their sins. The answer to their problems was to turn to God in a new attitude of faith and repentance, which they refused to do. Samuel warned that just as God had punished them for disobedience when they were under the judges, so he would punish them under the kings ( 1 Samuel 8:4-22; 1 Samuel 12:8-15).

Subsequently, the people got their king, and Samuel was no longer their civil leader. But he was still their spiritual leader, and he continued to teach them and pray for them ( 1 Samuel 12:23-25).

Just before his retirement, Samuel gathered the people to an assembly at Gilgal, and delivered a farewell speech or coronation speech in which he emphasised how prophets and judges were more important than kings, that kings should be held to account, and that the people should not fall into idol worship, or worship of Asherah or of Baal. Samuel promised that God would subject the people to foreign invaders should they disobey. However, 1 Kings 11:5, 33 and 2 Kings 23:13 note that the Israelites fell into Asherah worship later on.

Critic of Saul

When Saul was preparing to fight the Philistines, Samuel denounced him for proceeding with the pre-battle sacrifice without waiting for the overdue Samuel to arrive. He prophesied that Saul’s rule would see no dynastic succession. (1 Samuel 13:5-14)

Samuel also directed Saul to “utterly destroy” the Amalekites in fulfilment of the commandment in Deuteronomy 25:17–19:When the Lord your God has given you rest from your enemies all around, in the land which the Lord your God is giving you to possess as an inheritance, … you will blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven.

During the campaign against the Amalekites, King Saul spared Agag, the king of the Amalekites, and the best of their livestock. Saul told Samuel that he had spared the choicest of the Amalekites’ sheep and oxen, intending to sacrifice the livestock to the Lord. This was in violation of the Lord’s command, as pronounced by Samuel, to “… utterly destroy all that they have, and spare them not; but slay both man and woman, infant and suckling, ox and sheep, camel and ass” (1 Samuel 15:3, KJV). Samuel confronted Saul for his disobedience and told him that God made him king, and God can unmake him king. Samuel then proceeded to execute Agag. Saul never saw Samuel alive again after this. 1 Samuel 15:1-23

Samuel then proceeded to Bethlehem and secretly anointed David as king. He would later provide sanctuary for David, when the jealous Saul first tried to have him killed. (1 Samuel 16:1-12)

The remaining scriptural notices of Samuel are in connection with David’s history.

Decease and Traditions

The death of Samuel is described as taking place in the year of the close of David’s wanderings. It is said with peculiar emphasis, as if to mark the loss, that “all the Israelites” — all, with a universality never specified before — “were gathered together” from all parts of this hitherto divided country, and “lamented him,” and “buried him,” not in any consecrated place, nor outside the walls of his city, but within his own house, thus in a manner consecrated by being turned into his tomb (1Sa 25:1).

His descendants were subsisting at the same place till the time of David. Heman, his grandson, was one of the chief singers in the Levitical choir (1Ch 6:33; 1Ch 15:17; 1Ch 25:5).

The apparition of Samuel at Endor (1Sa 28:14; Ecclesiastes 46:20) belongs to the history of Saul. We here follow the inspired narrative, and merely say that Saul strangely wished to see Samuel recalled from the dead, that Samuel himself made his appearance suddenly, and, to the great terror of the necromancer, heard the mournful complaint of Saul, and pronounced his speedy death on an ignoble field of loss and massacre.

Character and Influence of Samuel

It is not without reason, therefore, that he has been regarded as in dignity and importance occupying the position of a second Moses in relation to the people.

In his exhortations and warnings the Deuteronomic discourses of Moses are reflected and repeated. He delivers the nation from the hand of the Philistines, as Moses from Pharaoh and the Egyptians, and opens up for them a new national era of progress and order under the rule of the kings whom they have desired. Thus, like Moses, he closes the old order, and establishes the people with brighter prospects upon more assured foundations of national prosperity and greatness.

In nobility of character and utterance also, and in fidelity to God, Samuel is not unworthy to be placed by the side of the older lawgiver. The record of his life is not marred by any act or word which would appear unworthy of his office or prerogative. And the few references to him in the later literature ( Psalm 99:6; Jeremiah 15:1; 1 Chronicles 6:28; 1 Chronicles 9:22; 1 Chronicles 11:3; 1 Chronicles 26:28; 1 Chronicles 29:29; 2 Chronicles 35:18 ) show how high was the estimation in which his name and memory were held by his fellow-countrymen in subsequent ages.

Bible References

- Miraculous birth of1 Samuel 1:7-20

- Consecrated to God before his birth1 Samuel 1:11,22,24-28

- His mother’s song of thanksgiving1 Samuel 2:1-10

- Ministered in the house of God1 Samuel 2:11,18,19

- Blessed of God1 Samuel 2:21, 3:19

- His vision concerning the house of Eli1 Samuel 3:1-18

- A prophet of the Israelites1 Samuel 3:20,21, 4:1

- A judge (leader) of Israel, his judgment seat at Beth-el, Gilgal, Mizpeh, and Ramah1 Samuel 7:15-17

- Organizes the tabernacle service1 Chronicles 9:22, 26:28; 2 Chronicles 35:18

- Israelites repent because of his reproofs and warnings1 Samuel 7:4-6

- The Philistines defeated through his intercession and Sacrifices1 Samuel 7:7-14

- Makes his corrupt sons judges in Israel1 Samuel 8:1-3

- People desire a king; he protests1 Samuel 8:4-22

- Anoints Saul to be king of Israel1 Samuel 9:10

- Renews the kingdom of Saul1 Samuel 11:12-15

- Reproves Saul; foretells that his kingdom will be established15" class="scriptRef">1 Samuel 13:11-15,15

- Anoints David to be king1 Samuel 16

- Shelters David while escaping from Saul1 Samuel 19:18

- Death of; the lament for him1 Samuel 25:1

- Called up by the witch of Endor1 Samuel 28:3-20

- His integrity as a judge and ruler1 Samuel 12:1-5; Psalm 99:6; Jeremiah 15:1; Hebrews 11:32

- Chronicles of1 Chronicles 29:29

- Sons of1 Chronicles 6:28,33

- Called SHEMUEL1 Chronicles 6:33

References:

https://wiki.bibleportal.com/page/Samuelhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel